Just five months after the launch of the 25-year Bicycle Strategy for Northern Ireland, work will start next week on the first dedicated cycle routes devised by Minister Michelle McIlveen’s DRD Cycling Unit. The initial sections of a cross-Belfast route and a major overhaul and extension of the infamous Bin Lane are expected to be completed by March 2016, costing up to £800,000.

Section 1 will connect three Belfast Bikes stations with a traffic-free protected cycle track, while obliterating the two most famous cycling infrastructure landmarks in Belfast, Cyclesaurus the idiosyncratic dinosaur tail cycle lane and the Bin Lane.

DRD to start work on 3 new Belfast cycle routes – due to be completed by March 2016. pic.twitter.com/IKzkjCLl0b

— Alana Taylor (@alanaciao) January 21, 2016

Sections 2 and 3 will create a new bicycle route servicing an area of the city with low cycling uptake. Sections 4 and 5 are due to follow by the end of 2016.

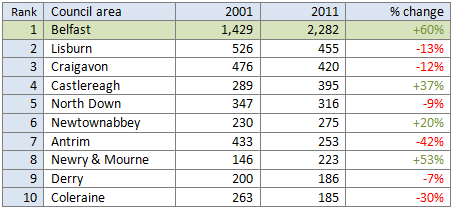

“These routes will provide greater protection for people who choose to make journeys across the city by bike. In addition to supporting the successful Belfast Bike Share Scheme they will also help more commuters gain confidence to use the bicycle as an alternative and sustainable mode of transport. My Department’s most recent figures show that 5% of Belfast commuters are already travelling to and from work by bicycle.”

Minister McIlveen

These are officially being treated as pilot routes, giving the Cycling Unit the ability to change elements which aren’t working or need improved. However, the high quality nature of the design shows a determination to set new standards, leaning on best practice from abroad, and the first application of London Cycling Design Standards in Northern Ireland.

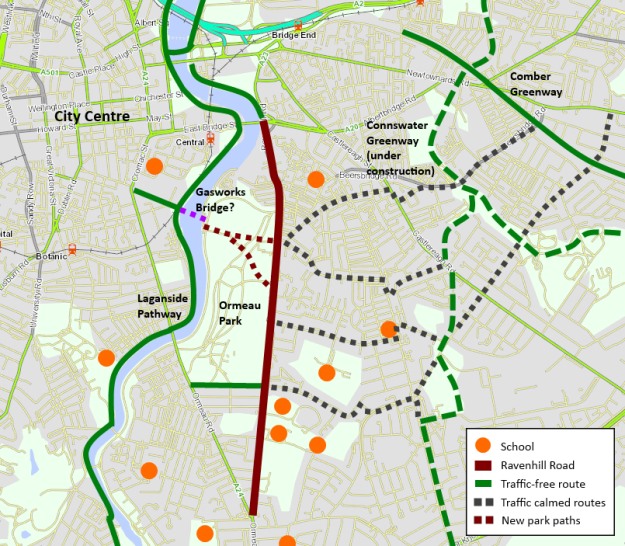

Section 1 – Ormeau Avenue to Chichester Street

Alfred St to be made one-way northbound with a cycleway protected by bollards extending the 0.5km from Chichester St to Ormeau Ave. This will create a 1.1km traffic-free route between NCN Route 9 and the city centre, linking four Belfast Bikes stations and sending a reminder about the need to build the Gasworks Bridge. It will finally obliterate the mess of Cyclesaurus, and reboot the Bin Lane to prevent the daily incursion of delivery vehicles from embarrassing Belfast.

Major implications: 4 @Belfastbikes docks to be linked by traffic-free city centre route (Arthur/Alfred/Gasworks x2) pic.twitter.com/Piu60PtnjO

— NI Greenways (@nigreenways) January 21, 2016

The Ormeau Ave entrance to Alfred St will be made into a continuous footway to prioritise pedestrian and cycling movements.

19 on-street parking bays will be removed to provide space for the new cycleway running past the entrance of the Premier Inn Hotel. Will this prove to be one of the more controversial elements of the plan? The popcorn is on standby..

The junction of Alfred St with Franklin St / Sussex Pl remains the busiest and riskiest junction for cycling on the route. Making Alfred St one-way reduces the total possible vehicle movements on the junction from nine to seven, and with continuous cycle priority across the mouth of Franklin St it may improve safety.

3 special #Cyclesaurus mugs now with @SustransNI, @thefredfestival and DRD as their #FredBad award pic.twitter.com/8yGaapZ3Md

— NI Greenways (@nigreenways) December 13, 2013

I suspect it won’t be long before Franklin St is stopped up to vehicles here, but that is a battle for another time and another (ongoing) consultation.

The May St junction will now have a straight-ahead view (removing the traffic pole clutter and cycling slalom effect) with separate crossing for those on bicycles and pedestrians. Vehicles emerging from Alfred St will now be banned from making left turns towards the City Hall. Given the crossing phase is likely to coincide with this green light, it will be most interesting to see if this is observed.

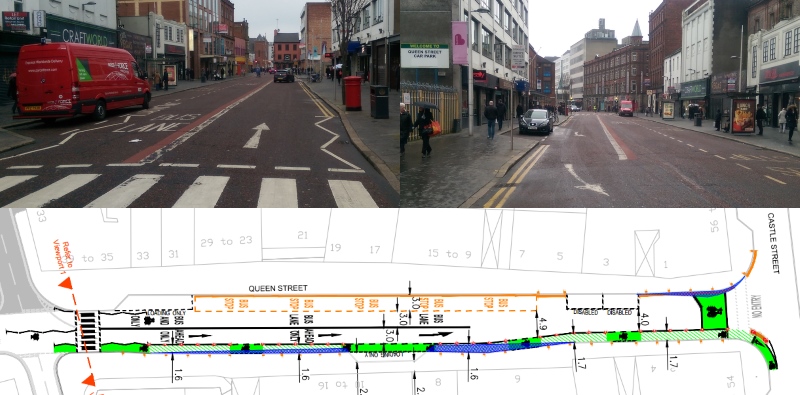

And then to the Bin Lane – why is work necessary to this kerb-separated cycle track? Just take a look at the #BinLane hashtag over on Twitter to find out. The kerb will be removed in favour of a consistent design approach of bollards along the length of the scheme. More controversy (and popcorn) but this time from cycle campaigners? The comments are open..

New loading bays created in place of paid on-street parking on Upper Arthur St (directly below a 472-space multi-storey, for context) will accommodate commercial needs. The intention of bin owners is unclear at this stage.

To misquote The Dark Knight, this protected cycleway is not the plan Alfred St and Belfast’s Linen Quarter deserves, but it is the one it needs right now. With more place-appropriate measures like side street blockages, removal of most on-street parking and cellularisation with area-wide one-way restrictions for motor vehicles, perhaps 90% of circulating and through-traffic could be removed from these streets.

That is the way to humanise the whole area – choked as it is by cars searching for on-street parking spaces – and would make separate space for cycling unnecessary. Any bollard v kerb debate should bear in mind that realistic end goal. But for now, until that plan can be argued for and achieved, mode separation will help to make cycling more attractive.

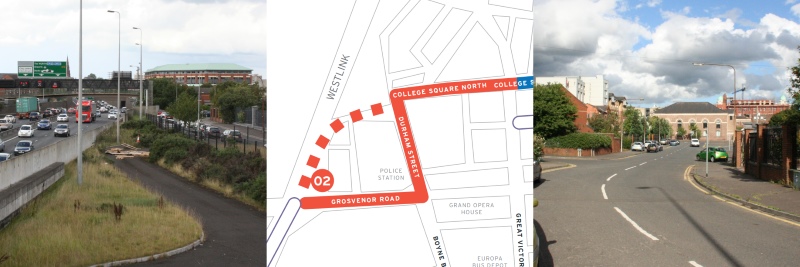

Sections 2 and 3 – Grosvenor Road to City Centre

This represents the first half of the cross-city route which will straddle the city centre from (almost) the Royal Victoria Hospital to Titanic Quarter Railway Station and the greenway network beyond.

Slightly disappointing is the Grosvenor Rd section itself, which will be a shared footway. Once the route is established and seeing regular bicycle traffic (which the expansion of Belfast Bike Hire further up the Grosvenor Rd to the Royal Victoria Hospital guarantees) the Cycling Unit should be given the budget to create a cycleway ramp to Wilson Street. This would significantly cut the journey time and amount of shared used footway on the route, and liven up an otherwise silent street choked with ‘free’ parking.

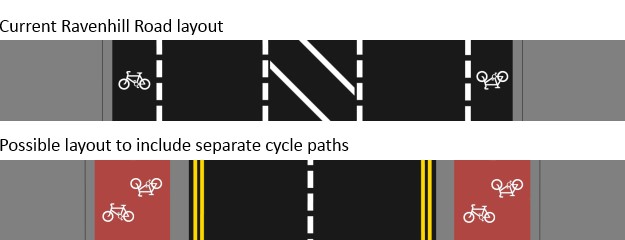

Around the corner to Durham St and the beginning of the protected two-way cycle track, to be built utilising roadspace rather than footway.

The mini roundabout at Barrack St (an earlier measure to reduce rat-running and to humanise these streets) will be replaced by signalled-controlled crossings, flipping bicycle users to a bollard-protected cycle track on the opposite side of the road.

At the junction of College Sq N and College Ave, a bold decision has been taken to rework traffic movements to create a bicycle priority junction. A low-level bicycle signal and dedicated crossing phase matching in with traffic turning left out of College Sq N will ensure bicycle users are treated like kings and queens of the road.

And over on College St, traffic mostly emerging from a surface car park will no longer have that option. The street is to be stopped up to vehicles, becoming a “bicycle street” with minimal interactions with vehicles expected. This again is radical, should be applauded, and will provide evidence for similar options around the city.

Onto Queen St and there is another bollard-protected cycleway – it may feel like overkill on a street which has seen so much traffic removed over the years, but serves a key purpose as a contra-flow to the one-way system for vehicles.

The wider plan is for a traffic-free route all the way from Falls Park, traversing (if possible) Bog Meadows, meeting the cycleway beside the Westlink (and very likely a branch into the new Belfast Transport Hub) then across the city to meet the greenway network which is currently spreading over East Belfast, and the ‘spine’ of Belfast cycling, the traffic-free NCN route 9 from Lisburn to Newtownabbey.

Sections 4 and 5 – High Street to Titanic Station

These last sections are planned to begin sometime in the Autumn and expected to be finished by the end of the year. The High Street section is undergoing a major rework following consultation feedback, but the impressive removal of a lane of traffic on Middlepath St to create a new two-way cycle track will still set a high water mark for cycling development.

The first act of Belfast's #cyclingrevolution will look a bit like this 🙂 #HOPE #Bikefast https://t.co/2sb6kXfhe6 pic.twitter.com/ZJ0MZh4Kcy

— NI Greenways (@nigreenways) August 27, 2015

The shadow boxing ends – the Cycling Unit is two years old, the Bicycle Strategy for Northern Ireland is now operational and we arrive at the Delivery Phase. Hallelujah!

It is important to set these route announcements in context – the Belfast Bicycle Network Plan and Bicycle Strategy Delivery Plan have yet to be finalised and published by the Cycling Unit. The Minister and her team should be commended for pressing on despite the scant budget at their disposal to date. If this project signals a Seville-like determination to just get on with building dedicated routes, the future for cycling in Northern Ireland looks bright.

*Note: the section drawing are not the final, final plans but an earlier version available here.

![Original ward map by Rathgarrr (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons JobsMDMBelfastWards6](http://nigreenways.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/jobsmdmbelfastwards61.png)

![Original ward map by Rathgarrr (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons WalkingPublicTransportBelfastWard5](http://nigreenways.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/walkingpublictransportbelfastward51.png)

![Original ward map by Rathgarrr (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons SustainableCyclingBelfastWard5](http://nigreenways.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/sustainablecyclingbelfastward51.png)

![Original ward map by Rathgarrr (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons CentreJourneyCarHousehold5](http://nigreenways.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/centrejourneycarhousehold51.png)

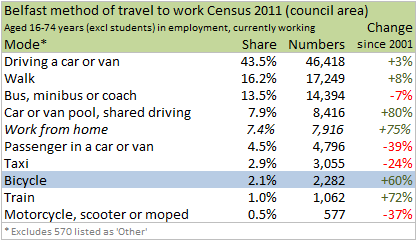

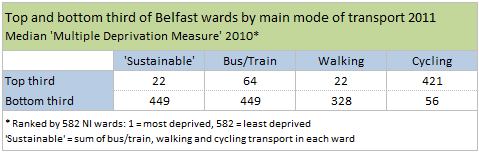

There are certain structural issues which influence main mode of transport choices in Belfast. The last map shows a close correlation between areas of high deprivation and lower percentages of household car ownership, and the opposite true of areas of lower deprivation. But the concentration of cycle commuting also closely matches areas of higher car ownership, so perhaps the assertion that bikes are luxury items in Belfast may hold some truth at present.

There are certain structural issues which influence main mode of transport choices in Belfast. The last map shows a close correlation between areas of high deprivation and lower percentages of household car ownership, and the opposite true of areas of lower deprivation. But the concentration of cycle commuting also closely matches areas of higher car ownership, so perhaps the assertion that bikes are luxury items in Belfast may hold some truth at present.